“You remember the lava game?”

She spoke in a voice for direct talk with her son. It wasn’t a baby voice. It was light but stern, like she was singing in a staccato and commanding cadence.

I sat on the couch, sank into its plush as I tapped the controller mindlessly. I opened a video app.

I’d been having trouble doing nothing since nothing was all there was to do. I played video games and scrolled timelines and sometimes did actual reading, though I found it difficult to achieve the peace required for books. We were already weeks into quarantine, though it was Ryan’s first quarantine week with his mother. The weeks prior, Ryan’s father had planned a trip for him, Ryan’s stepmom, and his son that just couldn’t be rescheduled even though parts of the world were already reeling.

“Yeah!” Ryan said with an excitement that felt obscene.

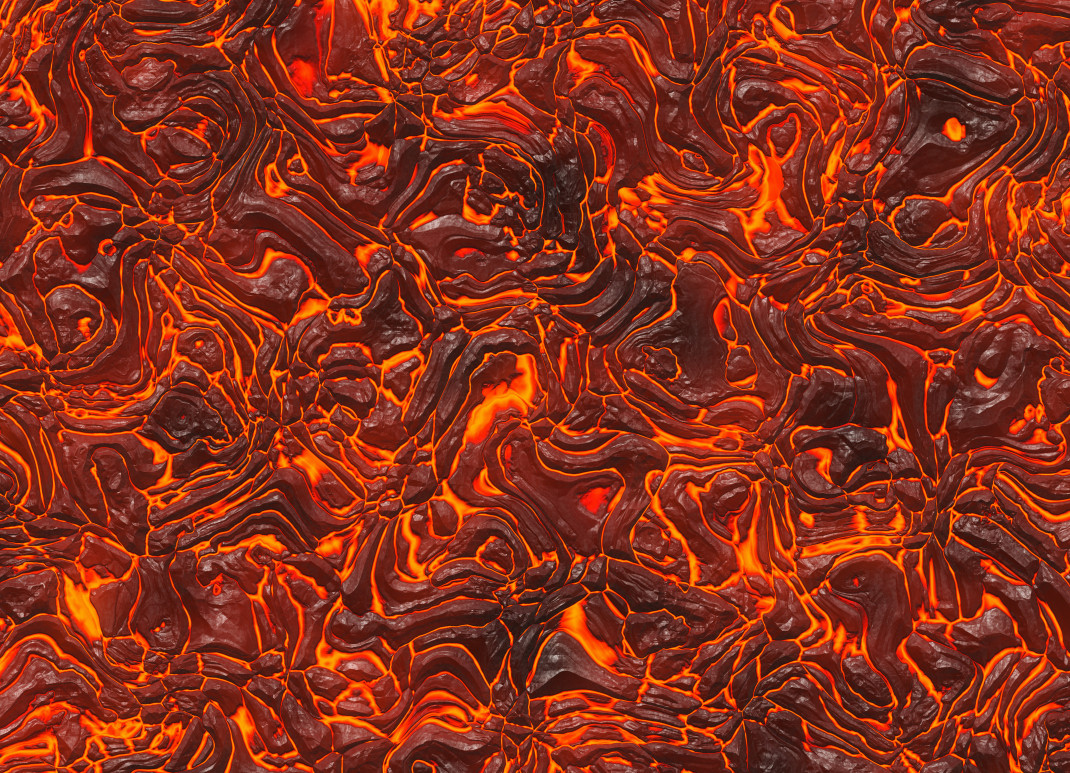

“Good,” Yani said. “Tomorrow we may have to go outside. I’m telling you now everything is lava. Your shoes are lava-proof, but when we go outside everything, everything is lava.”

She’d gotten down on her haunches so she could be at his eye level. I wondered if I should chime in some supportive words, maybe make a joke, cut the seriousness with something else. I said nothing.

“Do you understand?”

Ryan nodded.

“From now on, even your face is lava. Don’t touch your face either.”

“My face?” Ryan said.

“It’s—”

“Ahhhh,” he screamed and ran around the living room, his hands flailing in the air like his head was on fire. I watched him run frantic laps around the kitchen island. Yani wasn’t smiling, then she was.

“This is serious Ry—don’t touch your face.”

She took him to his room and he reemerged in his inside clothes.

“I’m gonna log in to work, okay?” she said.

I’d been around Ryan plenty. Still, the lack of additional instruction seemed like a vote of confidence. It was Spring Break, plus school was still in the process of transition to an online model, so time was his. I smiled and nodded at Yani. She disappeared into her room.

“Hey hey,” Ryan said.

He sat down next to me on the couch. His spirit completely unmired by all of it. I remembered that Yani’s son terrified me.

He liked me. Once, he’d seen me make four free throws in a row at the park.

“Did you play in the league?” he’d asked in wonder.

“I’ve played in a league,” I’d said, thirsty for his approval. Remembering that court full of running bodies made me jealous of our recent past.

“Wanna watch something?” I asked.

I’d been having trouble doing nothing since nothing was all there was to do.

In quarantine I learned random things on YouTube. It didn’t exactly decrease the sharpness of my depression or anxiety so much as it changed the flavor. The videos made the dread I felt pressing from all directions feel like a side effect of some far away but approaching genius.

We watched a video where an astrophysicist explained gravity to a child and then a series of individuals more and more well versed in physics. I don’t know why I chose it. It had the word “child” in the title. I panicked.

The physicist said, “The Earth pulls us down, but we also pull the Earth toward us in a way too small to feel.”

“Whoa,” I said.

“Whoa,” he parroted. He slapped his cheeks in exaggerated wonder.

“Don’t do that,” I said, instinctually. He looked at me confused, hurt even. “Lava, remember?”

“Everything is lava,” he said. He stared back at the screen.

“Exactly,” I said. “Be right back.”

I got up and went to the bathroom. I stared at the mirror. The face was mine and I tried to feel grounded in that observable fact.

“You aren’t having a panic attack right now,” I told myself. “It’s just hot.” I splashed water on my face, then dried the water with a towel. I washed my hands for thirty seconds. The day before, we’d been in bed. The silence throbbed. Yani, even in my silence, could feel my anxiety radiating.

“You okay?” she asked. “It’s okay to not be.”

I pretended to be asleep.

I returned to the couch. Ryan seemed invested in the astrophysicist that was now speaking to a graduate-level physicist.

“A teaspoon of a neutron star would weigh billions of tons here,” Ryan said.

“What’s a neutron star?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Ryan said. He added, “Gravity is also time.”

I looked at him and suddenly was laughing.

“I feel the same way, man.”

Now two high-level physicists flirted as they considered that which binds us all.

“What are you gonna do now?” Ryan asked.

“Huh?”

“Now that everyone is getting sick and we can’t touch anything.”

“Probably nothing,” I said.

“Mom’s scared. My dad too.”

“I think all the adults are scared.”

“Are you scared?” he looked at me. A man who’d played in a league. The fundamental laws of the universe became background chatter.

“I’m very scared. All the time. Even before I was scared. All this makes me feel normal almost, because I think—now everyone is feeling what I’m feeling all the time, except it’s not like that because I think I still feel a little worse than them.”

I looked at Ryan, wondered how much truth was appropriate for children.

“It’s okay,” he said. “It’s scary.”

The physicists on the television explained how there was almost certainly a multiverse.

“How you guys doing?” Yani appeared near the video’s end. She handed Ryan a box of raisins. She smiled as she handed me one, too. A red box.

“We’re scared,” Ryan said.

And when Yani looked at me I added, “Also, we’re learning about gravity.”

“I’m going to go argue with teachers more, okay?”

We both said nothing for a while.

“Neutron stars,” Ryan said.

“Yeah,” I said. And then we ate our raisins.