Look at this—a line of perfect dime-size pinhole-projected suns across my legal pad this morning. It takes me a minute to figure it out—I’m not in Dallas, where I live most of the time, but in the little town of Corsicana, Texas, about an hour south, where my wife, an artist, has a downtown studio and, a mile away, an old Victorian house where the dogs and I have joined her to wait out the pandemic and where I have a little writing desk in a corner with a window to my left, the south, whose ripply panes must be as old as the rest and whose accordion shade, half raised, has tiny holes where the cord goes through and through which holes the sun projects onto my pad. I love such accidental revelations. Most are not as clear as these—if there were a major sunspot group, I might detect it. Or an eclipse, I could observe right here—six tiny, deepening crescents. I draw a ring around each one and note the date and time. If it’s clear tomorrow, I will mark how much they drift.

I think as a child I pretty much took fear as a ground state. A default condition—from which all the items of experience emerged. The nonspecific background noise of life. Which may, of course, be how it is for everyone. Though eventually gotten used to, I suppose. A sort of tinnitus of the soul. You let it go. And after a while forget to hear it. So how strange out here, already so quiet, now with such a stillness further imposed, to pick it up again as when you realize the first cicadas of the season have been whispering for a while. Ah, there it is. Though I’m too old, too out of practice to respond in that visceral way. But there it is. Fear as a general thing. Dispersed and fundamental. As I feared. Right out of the ground like the cicadas. Here in Navarro County fifty-seven cases and two deaths so far. One keeps the count.

The projections seem to drift (as, over the next few days, I detect by noting spacing irregularities) not up or down the page in rank as I expected, but processionally to the left as beads on a string drawn at an angle across my desk. This I interpret right away—I see no other possibility—to indicate an increase in the rate of the earth’s rotation. That our fearful days and nights must be accelerating. And that even now, those living nearest the equator, where centrifugal force would be the most pronounced, might feel a certain loss of gravity. A sense of failed attachment. I am enchanted by the subtlety, the delicate indirection of my terrible discovery. Like ripples in the teacup at the tyrannosaur’s approach. I can’t imagine there is anything to do. And I wonder, sitting with my wife out on the porch in the evening, whether I should tell her. On top of everything else. She’ll find out soon enough, of course.

Well, there you go. Sprung loose. A fear so deep can seem almost ecstatic. That we find ourselves at last within a sort of whirling stillness in this strangely cloistered time.

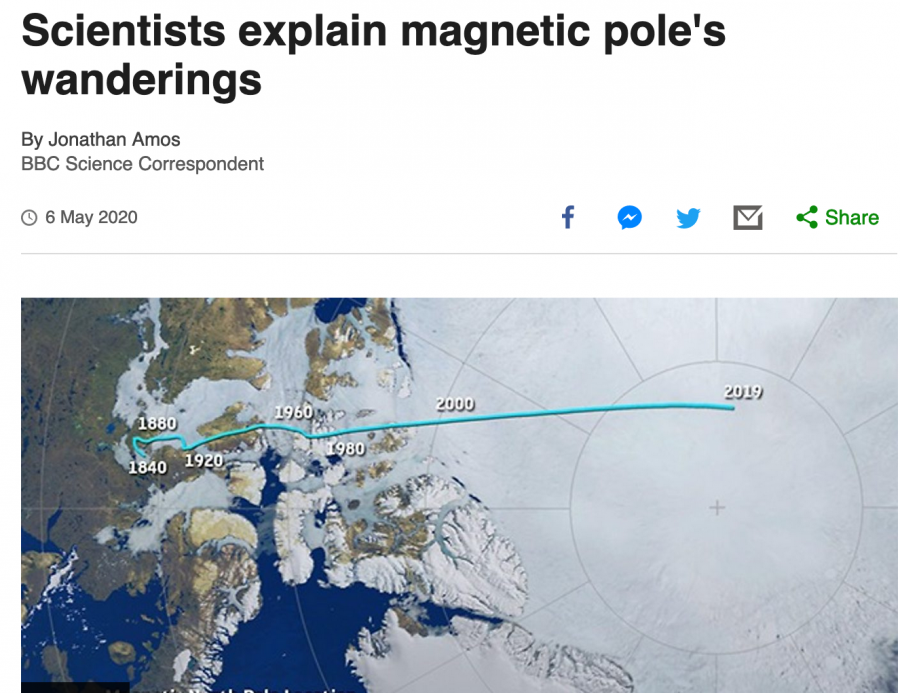

And it would seem unkind to ruin such a lovely evening with the prospect of such stillness giving way to such a lightness. People walking with their dogs, occasional cyclist creaking past will, at some point, find loss of traction a concern. The trains that come through here will make a softer rumble. Spiderwebs will find new forms. What could have happened? Something must have sprung loose, somehow. Like that time my pocket watch—a silly college affectation—fell from my pocket to the hard tile floor as I sat on the toilet dumbly staring down to watch the hands speed up, the gears beginning to whir away the hours faster and faster, life and hope escaping there within that sad, embarrassed, cloistered moment. Maybe something cosmologically like that. Or geologically—that thing I read about the recent shifting of the earth’s magnetic field. The rearranging of the molten core, I think. Well, there you go. Sprung loose. A fear so deep can seem almost ecstatic. That we find ourselves at last within a sort of whirling stillness in this strangely cloistered time. Like “whirling dervishes” I saw a number of years ago in Bursa on the Sea of Marmara. Spinning faster and faster, as it seemed, into a deeper form of stillness.

I will follow the projections, draw my circles, but say nothing for a while. And let our evenings on the porch acquire such lightness that the swifts seem borne on ever higher currents and the crickets’ song escapes us altogether. And I’ll count the deaths as those who lose attachment here and there to lift away like lost balloons.