He was a native, born and raised in Grand Rapids. He’d eaten donuts and hot cider out by the giant apple at Robinette’s, licking sugar crystals from his fingertips. He’d thumbed pennies into the electric ponies at Meijer, hoisting children and later grandchildren up onto the saddles. He’d carried children and later grandchildren piggyback through the sunlit corridors at Woodland, shopping for presents for birthdays. He’d walked the nature trail around Reeds Lake. He’d laid his palms across the Calder. He was a patriot, proud to live in Michigan, a retired carpenter with broad shoulders and a lumbering gait and a grip powerful enough to twist the nut off a bolt barehanded. His wife thought he was maybe not the most in touch with his emotions. He had bought a new vacuum the week before.

Now he stood in the living room, where one of his grandkids had just spilled a tube of glitter across the carpet. While his wife consoled the crying child, he got out the new vacuum. But when he flipped the switch, the vacuum didn’t power on. He tried resetting the outlet the vacuum was plugged into. He tried plugging the vacuum into a different outlet altogether. Nothing. One week old and the vacuum was already broken.

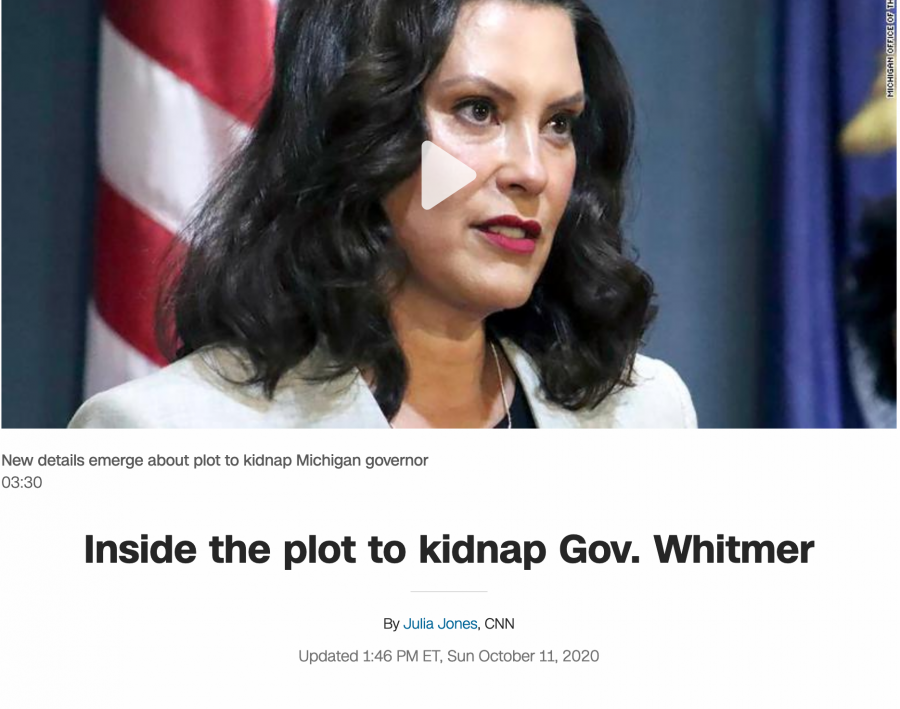

On the television, breaking news was playing on mute. A group of radical white terrorists had been caught plotting to kidnap the governor of Michigan. Reportedly the terrorists had been upset about having to wear face masks during what was literally a global pandemic. Crybabies with assault rifles. The screen flashed a photo of the alleged ringleader, a surly thug with a weak beard.

He yanked the vacuum’s cord from the wall.

“I’ll be back,” he said.

“Where are you going?” his wife said.

The vacuum shop was on Division, a street name that in recent years had come to seem quintessentially American. He parked the truck, strapped on a face mask, and then brought the broken vacuum into the shop. The sunlight was dazzling, making the windows glow. Behind the register, the owner was talking into a telephone. A customer in a pink sweat suit was waiting at the counter. He got in line.

He imagined the scene again, the terrorist sitting in dirty underwear on an inflatable mattress in the basement.

After a moment the customer at the counter swiveled to look at him.

“You seen the news about the militia?” the customer whispered.

He hesitated before nodding.

“The leader lived here,” the customer said.

“Grand Rapids?” he said.

“In the vacuum store,” the customer said.

He squinted in confusion.

“Under the floor,” the customer whispered, eyes wide, pointing down at the floor with a trembling finger.

The owner hung up the telephone, and then, seeming embarrassed, even ashamed, confirmed that the ringleader of the kidnapping plot had in fact lived in the basement of the vacuum shop. A middle-aged military veteran, the owner claimed to have been oblivious to what the terrorists had been planning, emphasizing that the terrorists had only ever met at the vacuum shop late at night, after hours. The owner had known the ringleader for years, had felt sorry for the ringleader, and had been letting the ringleader crash in the basement during a time of transition, and although admittedly the ringleader had recently amassed a concerning arsenal of weaponry, the owner had honestly never imagined that the ringleader was a traitor to the country, or that the ringleader would be foolish enough to attempt to overthrow the government.

“That’s really all there is to say about it,” the owner said.

The customer in the pink sweat suit asked a question about backpack vacuums and then left, and he finally stepped up to the counter. He explained the situation. He traded in the broken vacuum for a new vacuum. He pocketed the receipt. But all that time, although he was interacting with the owner, he was hardly paying any attention to what he was doing. Instead, he was distracted by the floor, suddenly hyperaware of the thin battered carpet under the soles of his boots, and how the floorboards beneath shifted under his weight, betraying the presence of the hidden chamber below. He remembered the cold rainy morning that he’d come into the shop the week before, and he imagined the scene again, but now from a new perspective: the terrorist sitting in dirty underwear on an inflatable mattress in the basement, surrounded by guns and ammo and tactical gear, as he’d walked across the ceiling of the basement, browsing the vacuums for sale, oblivious to the threat below. He’d known that he was upset about the kidnapping plot, but he must have been more upset than he’d thought, because imagining being that close to one of the terrorists made his heart pound, and he was struck by a sense of dread. As he carried the new vacuum toward the door, he felt a pulse of horror with every footstep, conscious of the fact that below the soles of his boots lay the dank foul den where a terrorist had eaten and masturbated and plotted mayhem and murder. He was faintly dizzy. He walked out the door, back out onto the street, and the door shut behind him, but even out on the street, standing there alone on the sidewalk, the ground seemed to conceal a menacing presence, and he looked out across the road and the intersection and the city beyond with a growing horror. He managed to stagger a couple of steps down the sidewalk, and then another wave of dizziness hit him, and he sank down onto the curb, fumbling the new vacuum and sitting there with his legs splayed out and his palms flat on the pavement, breathing way too fast. And in that moment he realized that the horror gripping his chest wasn’t a new feeling, but instead was a feeling that he’d been living with for the past five years, helplessly watching the daily news. As if there were crazed white radicals lurking beneath the surface of the entire city, and the entire state, and the entire country.

Concerned bystanders had gathered around him, looking down at him on the sidewalk.

“Are any of us safe here anymore?” he said, but nobody answered.