You may have felt, at times, that objects possess a spirit of their own. From your child’s stuffed animal to your grandfather’s cane, certain possessions accrete a life force. Which is to say that if you have ever walked up Madison Avenue between 63rd and 64th, on the east side of that block, and felt as though you were being watched from one of the many store windows, it is likely because you were. I am one of these sorts of objects, and one of three models—I prefer this term to the dehumanizing manikin—in the window of Le Petit Trianon, a boutique specializing in women’s fashion.

I have always marked time by the seasons’ collections, but this year has passed strangely. I do, however, remember what I was wearing at its outset, a yellow-belted Winter 2020 Carolina Herrera dress with a low scooped neck and tapered waist, which was lucky for me as it was a transition piece, one that could take me into spring and even into summer, as it nearly had to.

March into April, and April into May, the streets remained empty and the doors of our boutique remained shut. In these early days, the twenty-something-year-old sales associates would check in twice weekly, dusting and organizing, inspecting and reinspecting the backroom inventory, a vault crammed with hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars’ worth of designer clothes.

Eventually, though, Mirabelle had to furlough her sales associates. For a month, we saw nobody. The doors remained closed and the sidewalks empty. Then, toward the end of May, a half dozen men in a pickup truck arrived. Mirabelle paid them in what I could only imagine was near the last of her cash before they boarded up our windows. Only then, with the outside world blocked out, did Mirabelle strip off my yellow Carolina Herrera. She placed it safely away in a locked backroom and I remained in my window, where it was dark and I was naked, without even my view onto Madison.

I could decipher the events that followed mainly through their sounds. Crowds with their slogans. Police with their bullhorns and demands to disperse. The occasional and terrifying cascade of shattered glass from an un-boarded window nearby. Once, they pounded on the boards, their fists only inches from my face. Long silences followed these chaotic nights.

The boards came off for Fourth of July weekend. Attired in the latest Dior, I assumed that business (and thus life) might soon resume its normal course. Yes, those who passed outside remained masked, and, yes, the protests returned on certain nights; but in those early days it seemed impossible that a Dior (like the one I wore) wouldn’t soon find its way into the closet of one of those many women who had always sustained Mirabelle’s business, the women who lived above us on Madison, Park, and Fifth avenues.

Mirabelle clearly assumed the same. Opening the boutique each morning, her days seemed less like work and more like a vigil. After a first week and then a second without a sale, she began rotating our outfits. In no more than ten August days, I went from Dior to Channel to Tom Ford and then back to Dior, all to no avail.

I couldn’t tell if what I heard was a celebration or a riot.

Her banker, who in the past had bought his own wife gifts from Mirabelle, arrived on a September afternoon. He insisted that she had no recourse but to sell off her entire inventory at a discount (an impossible task) and pay her debts; otherwise, she would have to shutter Le Petit Trianon. According to him, a bleak forecast lay ahead. A second wave of the pandemic. Fears about the outcome of the election. “You should hear what they’re chanting at City Hall: A.C.A.B. Eat the Rich. I’ve never seen anything like this.” To which Mirabelle said, “There is nothing new except that which has been forgotten.” Mirabelle explained it was something Marie Antoinette’s milliner had once said about fashion.

After that day, I began to imagine myself as a sort of Marie Antoinette, sequestered in my own Le Petit Trianon with concerns of what I might wear to the revolution as opposed to whether the revolution might deal harshly with me and the Mirabelles of the world. Perhaps there would be no place for us. Our dwindling business certainly seemed to suggest this.

Early in October, on what felt like the first autumn day, two high-school-aged boys entered the boutique. One was handsome, the other less so. Both had dark, greasy hair and dirty fingernails. The handsome boy approached Mirabelle at her counter. Leaning over his bent elbow, he said he was looking for a birthday present for his girlfriend. Mirabelle was immediately skeptical. As she guided the handsome boy toward a small glass case that contained less-expensive accessories she thought he might be more readily able to afford, he struck her center-chest, knocking her to the ground, and grabbed a $20,000 Birkin bag, cradling it like a football as he rushed out the door.

That night the police arrived. After gathering the details and reviewing the security camera footage, they conceded there wasn’t much hope in finding the boys. Their precinct was overtaxed and chasing down a couple of small-time thieves was a low priority. When Mirabelle observed that a $20,000 bag was hardly small-time thievery, the officer simply shrugged and said, “It is on Madison,” and he then provided Mirabelle his badge number for her insurance claim and reminded her to file promptly. A week later, she received a check for 70 percent of the value of the bag, no different than if it had been bought on sale.

While signs outside reminded people to register to vote and inside the cable news called it the most consequential election in a generation, for us, everything depended on the Winter 2021 collections. At night, Mirabelle poured over the buyers’ catalogs. She made spreadsheets of what inventory she might purchase and compared that with her negative cash flow. Long after closing, she sat in the back office, agonizing over how she might keep the doors open at Le Petit Trianon, but the math kept coming out the same: She didn’t have enough.

She imagined her business closing.

She imagined an ignominious return to retail work, descending vertiginously through brands: Chanel, Ralph Lauren, J. Crew . . .

Then an idea came to her.

She placed an order online and locked up, keeping the boutique closed until the scheduled arrival date of her package.

The Monday after Halloween was the day before the election. Mirabelle came in early to make certain she didn’t miss the delivery; however, she waited until that night to cut open the single package. Inside was all she would order for the Winter 2021 season. If this didn’t work, if every other item of clothing didn’t fly out of the boutique, we’d be ruined.

She went back to her vault and laid out her inventory, the gowns and cocktail dresses, the bags and pairs of shoes, all of it arrayed in magnificent twinkling splendor as it sat behind the single-pane glass window.

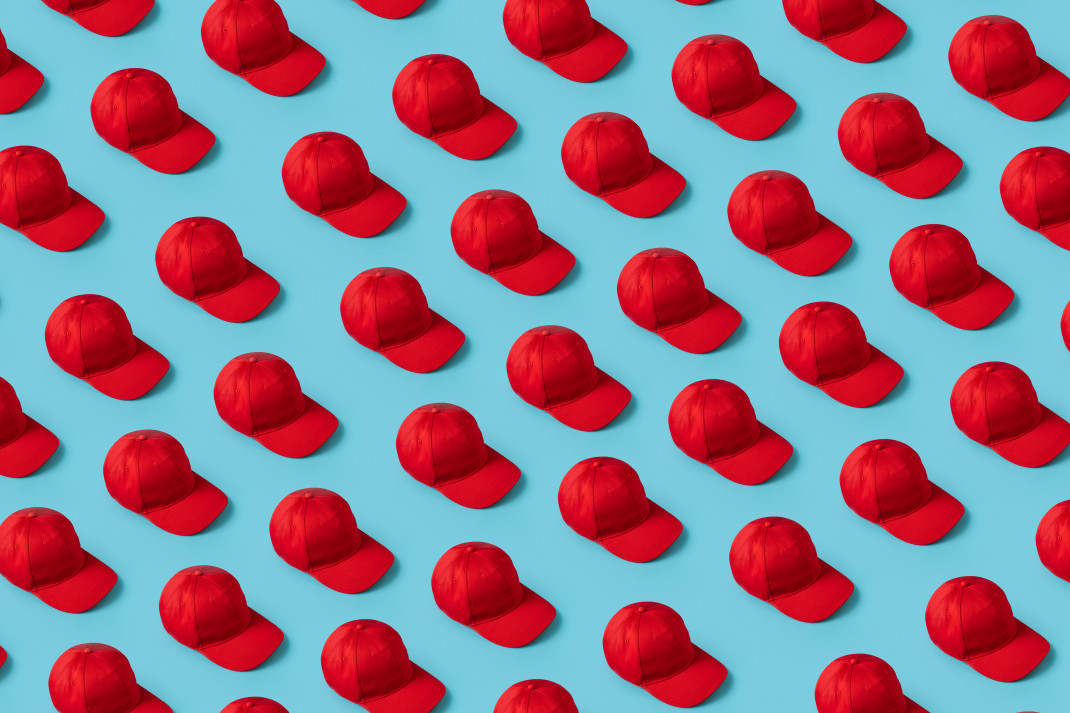

And then she opened the package that had come in the mail. Inside, I saw what she’d chosen: red ball caps.

She crowned each of us with one and left others in the window and locked the door.

As the polls closed and the results trickled in, a raucous crowd gathered in midtown. They had begun to march, heading in our direction; and I couldn’t tell if what I heard was a celebration or a riot as they approached steadily up Madison.